Munchausen Marriage

Werner Forman at a photo shoot

I never stopped to think what married life would be like with Werner Forman. I really didn’t know my partner very well, and from the beginning I could sense that things were going to grow stranger and more confusing with each day.

Werner atop an ancient site

I never stopped to think what married life would be like with Werner Forman. He was eccentric, I knew that. A small, nimble man who could climb an ancient ruin carrying all his camera equipment like a goat, who was obsessed with work and travel and never seemed to stay in one place for very long. At forty-nine years old, he was still extremely handsome with longish, fly-away hair, bright blue eyes, and a chiseled face that made people turn around and stare at him as if to wonder who this person was, and where they might have seen him before.

He spoke with a thick accent, mispronouncing many words. “Clothes,” for instance, in his mouth was “Clo-thus,” and “this” was “ziss.” But most of all he was mysterious. Up until this point, our lives had been totally about travel. Now, suddenly, we had a domestic life together, and I really didn’t know my partner very well. I didn’t know myself very well, for that matter, at the beck and call of an older, influential man who, because of his age and stature, I allowed to dominate me. I wanted to be a writer. I had always wanted to be a writer, and now I had the opportunity to quietly work on a bunch of short stories. We had moved into a large flat in Hampstead -- wood-planked floors, a big kitchen with a view over a beautiful back garden -- and here I’d install myself with a pack of cigarettes and my portable Olivetti typewriter. If I got very stuck for words, I’d sometimes also pour myself a wee glass of scotch that I’d park, just at my elbow, in case I needed it. In college I’d been a comp lit major, but I’d dropped out of school with one term left to go in order to be with Werner Forman. So I had no real credentials, was just a young pretty girl with a certain sophistication and a gift for words.

Nicole, early in the marriage (photo taken by Werner Forman)

Years later, I would wonder if Werner had married me for a green card. He was no fool.

I was the daughter of wealthy, art-collecting parents, and my businessman father was connected to all sorts of important people, including Senator Jacob Javitz who apparently ultimately pulled a string or two. If Werner went the green card route it would mean spending at least three consecutive months a year in the US. If he just went on living in London, he’d eventually accrue enough time for citizenship. In the beginning of our marriage, he tried to do both, and I got to experience, up close and personal, what a strange and mysterious man he was.

Werner Forman at a photography shoot

Werner Forman

First off, I had no idea what my new husband, Werner Forman, did all day. If I asked him, there’d be dead silence. He’d look at me like I was a fool, shake his head back and forth and change the subject. Or he’d start rapidly blinking his beautiful blue eyes, and launch a rant about a million things that might or might not have anything to do with the original question. All I knew was that he’d leave the house empty-handed each morning and return some hours later, most often carrying a small cardboard box.

At that point we were living in a large and very bare flat in Hampstead. I felt lucky to have found the place which was airy and spacious with floor-to-ceiling windows and a view over a pretty street. It had been advertised as furnished, but other than a bed, a living room couch and peasant-style kitchen table, there was nothing. We would have to supply our own. And so, when I learned what was in the boxes Werner brought home each day, I looked at our empty shelves and grew very excited.

Here’s how it would go. Without saying a word, Werner would open the box of the day and out would come a small, beautiful lantern or unusual vase or bright bead necklace or ancient wooden carving. He’d place the object on top of a tall stool, set up the lights he needed and photograph the piece from all sides.

Great, I’d think. Now he’ll put the vase or book or statuette on one of those glaringly empty shelves and things will start to look more homey. Wrong.

As soon as he finished photographing the piece, he’d place it back into its original box with the greatest of care and delicacy. He’d seal the box and carry it out to our hallway, which ran the length of the flat from front door to back bedroom and was extremely wide. He’d place it on the hall floor where it sat forlornly until the next afternoon when he brought another mysterious box home, one he’d place on top of the previous day’s box after photographing the treasure inside it.

Image: Kadarius Seegars

And so it came to be that our hallway was crammed with towers of boxes filled with gorgeous stuff while our walls and shelves remained empty. And still I had no idea where Werner went when he left the house each morning or why he refused to put his finds on display. I was a young girl who had married a man about whom she knew nothing. This was only the beginning and already I could sense that things were going to grow stranger and more confusing with each day.

Image: Andrew Gook

I eventually learned that if Werner didn’t have meetings with publishers on a particular day, he’d most often head over to Portobello market in search of treasures. There he’d wander for hours. But I never, in the eight years of our relationship, learned why he refused to put any of those treasures on display, why he kept them hidden away in tumbling towers of boxes like so many crazy old infirm relatives locked up and languishing in back bedrooms of grand old apartments.

There was a similar craziness in the way Werner handled people who came to visit. Every so often we would give dinner parties, usually inviting his publishers or editors or a friend or two of mine. I wasn’t much of a cook and my repertoire was pretty slim; I knew how to fry up onions, boil an egg, make a hamburger, but that was about it. I had one basic dish, consisting of ground meat, that I put together for dinner parties, but mostly we counted on ample quantities of booze to mask my culinary inadequacies. On the day leading up to the party, Werner and I would work as a team to get things ready, dusting, vacuuming, shopping for food, laying out glasses and silverware, preparing hors d'oeuvres and veggies and batches of rice. He seemed every bit as enthusiastic as I was, willing to run last minute trips to the shops for items I’d forgotten or to spend a couple of hours on flower arrangements. When the guests arrived, he’d greet them one by one, saying, “Hullo, hullo,” in his gruff voice, shaking hands, helping them off with their coats.

But no sooner were they all assembled than he’d put on his own coat and slip out the door, a mysterious-looking man in dark clothes with a book (probably) hidden in one of the pockets and a face filled with purpose.

The guests were usually too polite to ask where the hell he’d gone, but there was quiet murmuring and consternation followed by a large consumption of wine and whiskey. The weird thing was, most of these people were connections of Werner’s, not mine. If we hadn’t all gotten drunk to the point where everything seemed hilarious, it would have been extremely awkward.

Image: Askar Abayev

What was even more awkward was that, at the end of the evening, around midnight when the guests were in the hallway, putting on their coats, the front door would fly open and in would sail Werner, smiling and shaking hands with everyone and saying he hoped they’d had a good time. If someone asked where he’d been, his smile would deepen and he’d say in a sing-song voice, “Oh, I couldn’t possibly tell you zat.”

He certainly wouldn’t tell me, no matter how much I begged him, and after the first few dinner parties, I gave up asking. By now Werner’s behavior was impinging on all my friendships and I was beginning to suffer.

Werner & Nicole in the early days

Werner & Nicole with her parents, who were only a few years older than Werner

There was a twenty-five year difference in age between me and Werner. I was in my early twenties, a young girl who already was beginning to drink too much. Werner, entering his fifties, looked handsome but definitely older with silvery hair and a lined face. On numerous occasions, people got our relationship wrong, addressing Werner as if he were my father, as in: “You sit here young lady; this chair is for your dad.” Out in public, I was constantly steeling myself for remarks like that, remarks that Werner would blithely ignore, but that I would find mortifying.

But deep down Werner was acutely aware of our age difference, and almost from the beginning that awareness had devastating effects on my friendships, of which I had quite a few -- my college roommate had moved to London around the same time I had, as had my oldest friend on earth, Celia, who’d grown up across the street from me. There was a little group of us who’d been to school together plus I had family living in London, so I knew lots of people. And Werner, a loner who was jealous of every connection I had, didn’t appreciate that.

Early in our relationship we were guests at a dinner party given by an art dealer in Paris. There were perhaps ten of us and I was seated next to a handsome young man who was about my age while Werner was placed beside an older person further down the table. Not wanting to arouse jealousy, I tried to talk to my dinner partner as little as possible but that was difficult as the guy was chatty and I spoke fluent French and didn’t want to appear rude.

After the event, back in our hotel room, Werner refused to talk to me. His face was cold and expressionless and not a single word came out of his mouth; in fact, he pretty much acted as if I wasn’t there -- all because I’d been placed beside a handsome young man at a dinner party.

That sort of behavior became typical. Out to dinner with friends, my mind would be half on the conversation and half on, uh oh I was going to be late getting home and I’d better call Werner. So I’d get up from the table in search of a phone and in a sweet wifely voice let him know I’d be back by ten-thirty. But ten-thirty would come and go, so I’d have to get up again with a new ETA of eleven o’clock. And then eleven-fifteen. When I finally did get home, the apartment would be silent and dark and I’d find Werner in bed pretending to be asleep, his body rigid with fury.

Edvard Munch Lithograph

Werner sulking

Werner’s anger at me over my social life, such as it was, and the time I spent with friends became the bitter theme of our marriage. He simply couldn’t bear my paying attention to anyone else, and he would make me suffer for it by applying the silent treatment -- a kind of verbal shunning that could go on for days, leaving me miserable and unsure of myself.

I was a sitting duck for that. Instead of standing up for myself and the way I led my life, I felt guilty and was constantly making apologies and excuses, which of course caused everything to become much worse. We were two adversaries instead of a happily united couple. We would still have moments of sweet togetherness, but these were increasingly rare. On the up side, Werner was proud of me, non-judgmental and supportive; on the down side he was overly possessive and jealous. He had infinite faith in me as a writer and was always sending jobs my way. And if he got mad at me for my friendships, he had nothing pejorative to say about my drinking. In fact, he claimed people drove better with a little whisky in them, and when I once got stopped and briefly arrested for driving under the influence, Werner became furious at the police. (I had neglected to turn on my headlights, and was given a blood alcohol test that eventually proved me under the limit.) He never chewed me out about that, never said anything about my hangovers or drunken stupors. Instead he would surprise me by suggesting I write copy for his next book, whatever that happened to be. Up until then I hadn’t published very much, just some poems and a few short stories in small press, so no way was I ready to tackle a book about Islamic cities or the power of prophecy.

But the subject of prophecy fascinated me. I’d never been to a psychic before. When Werner started talking about doing a book on psychics, I practically ran to London’s Society for Psychical Research to sniff around their library. There I learned that whole families would make appointments with psychic mediums in order to contact loved ones who had passed on. I decided to make an appointment myself. I was assigned an older man with a BBC accent whom I’d never seen or met before.

He stared at my forehead, rubbed his hands together and told me four things: that I was a writer but it would take me years of hard work before I had success, that I was married to a photographer, that my husband had been involved with a blond woman, that my marriage would soon be coming to an end.

He told me these things without my asking a single question, and he was right about all of them.

From left Werner, Nicole, Franyo

Werner had two important female connections in his life who were both fourteen years older than he was. One was my mother, and the other was Trude, the blond woman the psychic had mentioned, who had been Werner’s girlfriend from the early 1950s until he met me. With Trude, whom I respected for her wit and candor, I developed an easygoing friendship; with my mother, oddly, it was more as if we were rivals for Werner’s attention. From the very beginning my mother, Franyo, had had a kind of crush on Werner. Her first remark about him had been, “I’d put my slippers under his bed any day,” a rather strange comment from a supposedly happily married woman to her daughter.

Franyo would come to visit us in London and stay for a month to six weeks at a clip. She would book into a hotel in Swiss Cottage, just down the road from us, and her days would be spent running around with Werner, visiting Portobello market and various antiques stores and art galleries. For me this was a great relief as it meant I could be free to do my own thing, which meant sequestering myself in the flat and working on whatever short story I was struggling with at the time.

Franyo would literally “doll” herself up for her jaunts with Werner, putting on lipstick and eyeshadow, a nice dress, behavior that didn't go unnoticed by friends and family.

I’ve written a lot about Franyo, including a memoir (The World of Franyo) but for those of you who don’t know, she was a German Jewish refugee who emigrated to the States in 1938, a spoiled, narcissistic and extremely good-looking woman who was also a gifted painter. My father would remain in New York while my mother traveled to London, and I believe that for him Franyo’s absences were probably a reprieve since he didn’t have to deal with her or her whims.

Nicole’s father, Gustavo

This was an interesting setup for sure. Perhaps the most interesting part about it was how easily I accepted my mother’s crush on my husband… and that husband’s willingness to play along with her. In private, Werner would talk about Franyo’s foolishness and silly schemes, but when he was with her he’d butter her up shamelessly, siding with her against me -- the sappy daughter. True, Werner and Franyo shared a European background and culture that was closed to me. But in effect, there were three of us in the marriage and I was quickly reaching the point of wanting to find a way out.

Image: Ava Sol

Image: Bedrich Forman art | obrazie-gallerie.cz

One morning when I was in my late twenties I woke up with a burning desire that hadn’t been there the night before: I had to have a baby. I wasn’t a particularly maternal person. I’d always assumed I’d have a child someday, but that was in the distant future, not something I had to focus on anytime soon. But suddenly it was all I could think about, almost as if I had turned into someone else, a woman obsessed with her fertility.

The only problem was, Werner didn’t want a child and never had. He was totally stubborn and unbending about that. I began to see that there wasn’t a single thing I could say that would change his mind, not even pointing out the sad fact that, due to our age difference, I would surely outlive him, and progeny from his loins would certainly make me feel less lonely in later life. In my misguided way, I thought having a baby would save our deteriorating marriage, so I plunged ahead in my mission, not particularly concerned about the repercussions.

To be fair to myself, I warned Werner, telling him that I intended to get pregnant no matter what. He didn’t seem particularly concerned. I had had my IUD removed several months earlier, but now I cut a hole in my diaphragm. When that didn’t produce results, I simply stopped using the diaphragm altogether.

Weirdly, Werner didn’t seem to notice. He didn’t resort to condoms either, and within three months I was pregnant.

Nicole in Hampstead

When I told Werner, he nearly had a nervous breakdown. He had a history of what I felt were fabricated maladies -- stomach aches, migraines, dizzy spells. It took me the first few years of our marriage to realize he was a hypochondriac and not to treat any of these ailments with too much concern. But his reaction to the pregnancy -- anger, sulking, disappointment, emotional shutdown -- was beyond anything I’d experienced with him before, and it was a relief when he announced he was leaving for a three month trip to Indonesia and the Philippines. I was just under four months pregnant and still not showing when he left. By the time he returned, I was entering my seventh month and big as a barn.

Image: Chayene Rafaela

Image: Alexander Krivitskiy

Curiously, Werner and I got along extremely well from the seventh month of my pregnancy till I went into labor three months later. Because I’d had some cramping and bleeding at sixteen weeks (due to my conviction that it was fine at that point to smoke and drink alcohol), I was considered a high risk pregnancy and had to spend a lot of time on bedrest. And the more you lie around in pregnancy, the bigger you get -- so there I was with a belly like the prow of a ship.

To prepare myself for labor, I’d joined a small Lamaze class. There were six of us, and all but one were American (the odd woman out was Irish). Except for me, we were all due at about the same time (I was due three weeks after the others, in mid-May). The Irish woman’s belly was bigger even than mine, and when she had a stillbirth on April 15, my birthday, I went nuts. I decided I simply could not wait another three weeks, couldn’t go through all that fear and frustration, had to give birth ASAP. And so I did something I’d never done before: I focused my mind so intensely on a desired outcome that the world dropped away and there was just me, standing still as a statue at the kitchen counter, and nothing else but a dim whoosh of light. Presumably I was deep in prayer. But this was different from prayer: stronger, all-consuming, a little bit shocking. The moment passed; my body felt as huge and pregnant as it had all of this final trimester. But when I went to the bathroom about an hour later, I saw a thin line of blood in my underpants and suddenly my large body seemed -- hormonally speaking -- to take a nosedive, as if I were a plane coming in for a crash landing. I remember thinking, What have I done? And I remember being terrified.

My daughter, Jofka, was born two days later. It was a straightforward birth, sixteen hours of labor, no drugs except at the very end when a med student stuck his hand up my birth canal in the middle of a contraction and I started screaming.

Werner came to visit me early in labor and when I kicked my feet in pain, he said, “Vat you have is normal. But I have sto-match ache and that could be serious.”

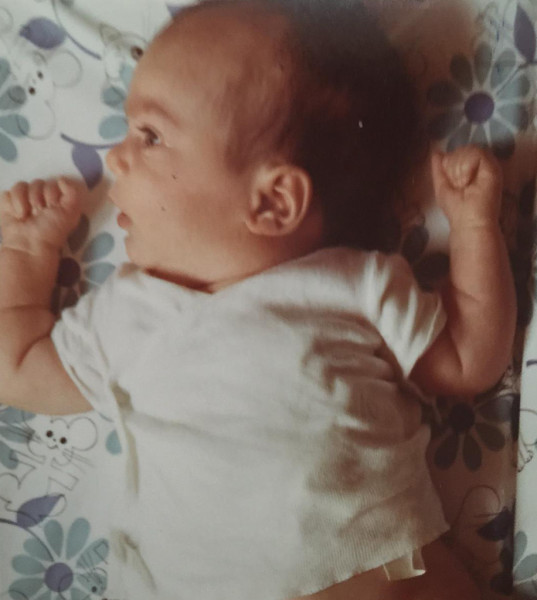

Baby Jofka

Typical Werner. He seemed happy to meet his daughter, walking around her crib moments after she’d been born, clutching his briefcase and staring at her out of his bright blue eyes in awe and amazement. It wasn’t till the next day that the troubles began.

Edvard Munch’s “The Scream”

At the time Jofka was born, in the spring of 1973, first-time mothers were expected to remain in hospital till ten days after their child’s birth. For most mothers, this was a deserved rest and they were okay with it; but for me, married to Werner Forman, it became very difficult. Guests would arrive, wanting to visit me and the baby. Well, they could visit me all right, but seeing the new baby was a different matter.

Werner, who had been so opposed to having children, would not allow his child out of the nursery during visiting hours for fear of germs (pronounced “gairms” with a hard G). All the other mothers would have their babies happily on display either in their arms or in bedside cribs, but there was me, empty-armed, with Werner, who was there every single visiting hour, beside me, and when guests asked, “Where’s the baby?” I’d be hard pressed to explain. The situation was extremely awkward. The nursery in that particular maternity home was hidden, not behind plate glass where guests could view rows of cute new infants in pink or blue, but in another part of the ward. My guests would arrive and there’d be no baby, just me, the incredibly nervous, stressed-out mom. And of course, Werner, the new dad, proud and in control. We’d make small talk. It was horrible and I couldn’t wait to get home.

But at home other horrors awaited me. From the beginning I loved being a mom. The baby suckled easily, I had plenty of milk and took the middle-of-the-night feedings and lack of sleep in stride. Back then we still used cloth diapers, so I became inured to the stink of the diaper service bag on the doorstep and the prick of pins.

But it wasn’t the new baby that was the problem; it was Werner. No sooner had we arrived home than he proceeded to have a Munchausen style nervous breakdown.

He took to the bed, wouldn’t get out of his pajamas, wouldn’t leave the house. Suddenly I had two children. He would say he had headache, stomach ache, dizziness, nausea -- whatever the malady made no difference as I was the one who had to care for both him and the new baby. But I took this in stride as well, not stopping to wonder what the hell was going on, not daring to ask questions.

Image: Armin Lotfi

I think my post pregnancy hormones kept me high and blissed-out. When he did get out of bed, Werner would have nothing to do with the baby. I seemed to be living on two tracks. It took my mother, who arrived six weeks after Jofka’s birth, to fix the situation.

Edvard Munch Lithograph

Nicole & Jofka

Just by virtue of my mother’s presence, Werner snapped to and once again became a functional human being. He began, openly, to handle the baby -- not to change her diapers, but to pick her up out of the crib and hold her, a mixed blessing as the months passed because he became so bossy and controlling about her care. In Werner’s opinion, for instance, breastfeeding should only continue the first year, and he became furious when he walked in on me nursing Jofka after she’d turned one. I loved the early morning feedings and was loath to give them up, another crack in the marriage.

But by now the marriage was doomed. I had fallen into a classic trap, thinking the birth of a baby would save it; instead, the marriage deteriorated, and I reached the point where I could barely stand being in the same room as Werner. Over the summer of Jofka’s second year, I traveled to the States to spend time with my parents in a rental house in East Hampton. The house was on a bay, overlooking a small marina. One night, after the rest of the household was in bed, I took a glass of wine and went outside to stand at the edge of the property. Beneath me, there were signs of activity on a small sailboat that had been covered since I’d arrived at the house. A man in jeans and a T-shirt was pulling off tarps. He saw me peering down and waved. Then he called out, asking if I’d like to join him for a glass of wine. His name was Yaacov, a trim, sexy Israeli, about thirty-five years old. We flirted outrageously and by the next day he made himself at home in our house, charming my parents and using the kitchen and bathroom for his own purposes. Nothing ever happened between me and Yaacov, but I had a vague crush on him, an attraction that led to the final demise of the marriage -- I just didn’t want to be with Werner anymore. Perhaps I didn’t want to be with anyone.

I’d spent years married to a man whom I allowed to dominate me and it was time to break loose, start a new life, be with younger people.

The problem was, how to tell him?

In the end, walking up Third Avenue in Manhattan, we had a very frank discussion. Werner asked if I still loved him and I steeled myself and said no, not in the same way as in the beginning. And that was it. I spent the summer in New York. A friend offered me a job teaching writing in the Massachusetts prison system and I accepted, even though I had no credentials whatsoever. Without too much thought, I moved to Cambridge where I found a house for me and Jofka, and started a job visiting prisons all over the state of Massachusetts. It would be a time of misery. I’d spent eight years with a difficult, brilliant man who totally controlled my life, and now I was free to explore a new kind of existence, one that would involve a growing addiction to alcohol even as I went on to complete my education and begin a long sought-after career as a writer. As for Werner, he continued his close friendship with my mother, and, until he became quite old, continued to live in the small house we’d bought together in West Hampstead, a house that became so overrun by Werner’s towers of boxes that he eventually had to leave it and move into a residential hotel. And there he remained, in a room gradually filling with boxes, a stooped, elderly man whose mind had failed and who no longer remembered the years he’d spent with me, or the fact that he had a daughter.

Nicole & Jofka

This story was originally published in ten parts on July 6, 2021, on nicolejeffords.com.