Adventures in the Real World

After life on Fayerweather Street, I got a job writing newsletters at a commodities firm in downtown Boston. I didn’t know a single thing about commodities or futures but quickly became an “expert” in the eyes of the shady salesmen. In truth, my ignorance in finance wasn’t the only thing I was hiding back then. There was also my growing addiction to alcohol and the forbidden love affair with a fellow group therapy patient.

Image: Jingming Pan

Image: Sora Shimazaki

I had graduated with an MFA in creative writing from Boston University, working with such greats as Stanley Elkin and Rosellen Brown. The big question was, what was I going to do now that I had my degree? I could teach as an adjunct, something I tried and was disillusioned with as it meant driving to a distant site, in this case Fitchburg, Massachusetts, for very little pay. What jobs were there for writers if one wasn’t a teacher, journalist, PR person, or researcher of some sort? I racked my brain. Hospitality was a possibility (not really, I just liked talking to people), but when I went around to different hotels with my flimsy resume there was no interest. I figured with my luck I’d end up selling lingerie at Filene’s. But then, out of the blue, someone told me about a commodities firm that was looking for a writer. I had no idea what that meant, but immediately called and made an appointment for an interview.

The person who interviewed me was a Mr. Ron Schaeffer, and I remember him clearly -- a middle-aged man with thinning brownish hair in a blue shirt and grey business suit that wasn’t nearly as crisp as it could have been. There was something about his face that was blurry, as if the bones beneath had begun to disintegrate. He looked at me out of kind blue eyes that had the same blurriness as his face, eyes that engaged but then seemed to turn inward as his attention drifted. This was the owner of the firm.

We had a nice conversation that first day. I was tense as hell, but Mr. Schaeffer could have been talking to someone he’d just met at a cocktail party -- about the weather, some blah blah about Boston, the fact that he’d grown up in Connecticut just across from where I’d grown up on the Long Island Sound. I don’t think we discussed any of my particulars other than that I was a single mother. I don’t think we even discussed the particulars of the job. In the end Ron said, “Well, Nicole, you say you can write.”

“That’s right,” I said, vigorously nodding my head.

“Well then, what I’d like is for you to write a report on gold.”

Uh oh, I thought. What in the hell did I know about gold other than wearing jewelry? “Okay,” I said.

“I’ll pay you $100 for your effort. Please have the report here a week from today.”

“Of course,” I said, already panicking because while I sort of knew how to write short stories, I wouldn’t know what a business report looked like if it came up and bit me in the ass.

But I needed the money and was willing to try.

Image: Pexels - Cottonbro

Nicole’s father, Gustavo

In 1978, one hundred dollars was worth quite a bit of money and I was willing to work hard on my report for Mr. Schaeffer to earn it. To this day, reading anything financial is like attempting to tease out words in Greek or Chinese, neither of which I understand. I simply had no idea what I was doing, and so, as I usually did in extremis, I picked up the phone and called my dad, a businessman who could’ve written a report on gold in his sleep.

I think I secretly hoped he would write the report for me, but instead he gave me a bunch of ideas, most of which I didn’t understand very well, and helped me concoct the opening paragraph. I also had help from the man I was currently seeing, a Carl Mendel whom I’d met in group therapy. Our involvement was, of course, a no no, and so we kept it secret, but the strange thing was we were both active alcoholics and no one in the group, including the leader, had figured that out. (I knew because Carl had shown up drunk one time, slurring his words and talking much more than usual.) Carl was a mathematician whose father had won a Nobel Prize in the same field, and so I was confident he could help me write the damn report if necessary. But as it turned out, after a few glasses of scotch to warm up my brain, the words started rolling out of me and I produced what may have been a killer document.

A week later I brought the document to Ron Schaeffer at his commodities firm, as instructed. I was wearing what I hoped would pass for a business suit, a skirt and some sort of jacket plus low-heeled shoes and a strand of pearls. My hair was short at the time, cut in wiry black waves that fluffed up around my ears and went in all directions -- not a great look for me. I was ushered into Ron’s office, clutching the report in its folder. Even though he wasn’t a particularly formidable sort of person, I was extremely nervous as I sat down across the desk from him. My mouth had become very dry and I wished I could light a cigarette.

Ron looked up and studied me with a totally blank expression. He smiled a tentative smile. “What’s this?” he said as I placed the report on the desk. He seemed honestly not to know.

“It’s the report on gold that you asked me to write,” I said.

Ron’s face expressed nothing but confusion. “I’m sorry to tell you this,” he said, “but I have no idea who you are, and I don’t remember ever asking you to write a report on gold or anything else.”

Dee dee da da dee dee dee … this was a true twilight moment and now it was my turn for utter confusion.

Image: Muillu

Image: Pexels - Cottonbro

I was totally stunned. I had just handed Ron Schaeffer my report on gold, a document he’d requested, and he had no idea who I was.

Now, as I sat across from him feeling as if I’d just stepped through a door to another, perplexing world, he told me that he suffered from a neurological condition that affected his memory. From moment to moment he would forget plans and activities that had been very solid in his brain half an hour before. He put his face in his hands as he said this, the picture of embarrassed humility. I didn’t know what to say, so I sat there in stiff silence. “Very few people know about my problem,” he continued, “and I’d like it to remain that way.”

“Of course,” I whispered.

Then he said, “I’ll read the report, and if I like what you’ve written I’ll get back to you.”

I guess his memory function worked well enough for him to remember to read the goddamn thing because the next day he called and offered me a job: one newsletter a month plus occasional reports on gold, silver, copper, sugar, etc. for a salary too generous to refuse. Okay. I was down for that although I was in the dark as to what any of it meant. I didn’t know a single thing about commodities or futures, but I figured I hadn’t known anything about the prison system either when I’d started working there a few years back, so I’d be able to manage this, too.

I liked it that I had to dress up in a suit and drive to an office in downtown Boston everyday. That made me feel important, less like an erstwhile student and struggling writer. I had my own personal office and a “secretary” who’d bring me coffee and type up my reports if needed. Once Ron discovered I had a genuine capacity to write about finances, he began piling it on.

From one newsletter a month, we went to one every week. And I had to be ready to do instant updates on any given commodity. I’d think I was done for the day and my immediate boss, a guy named Hank with a grey crew cut and humorless face, would stick his head in my door and say, “We need a quick update on Sugar. And make it look good.”

Make it look good. That meant, in reality, sugar was performing badly but I had to write some bullshit about how well it was doing on the market to get the firm’s customers to spend a few more of their hard-earned dollars on a crappy commodity. Hmmm. I started wondering what was really going on here.

Image: Francesco Ungaro

Image: Suzy Hazelwood

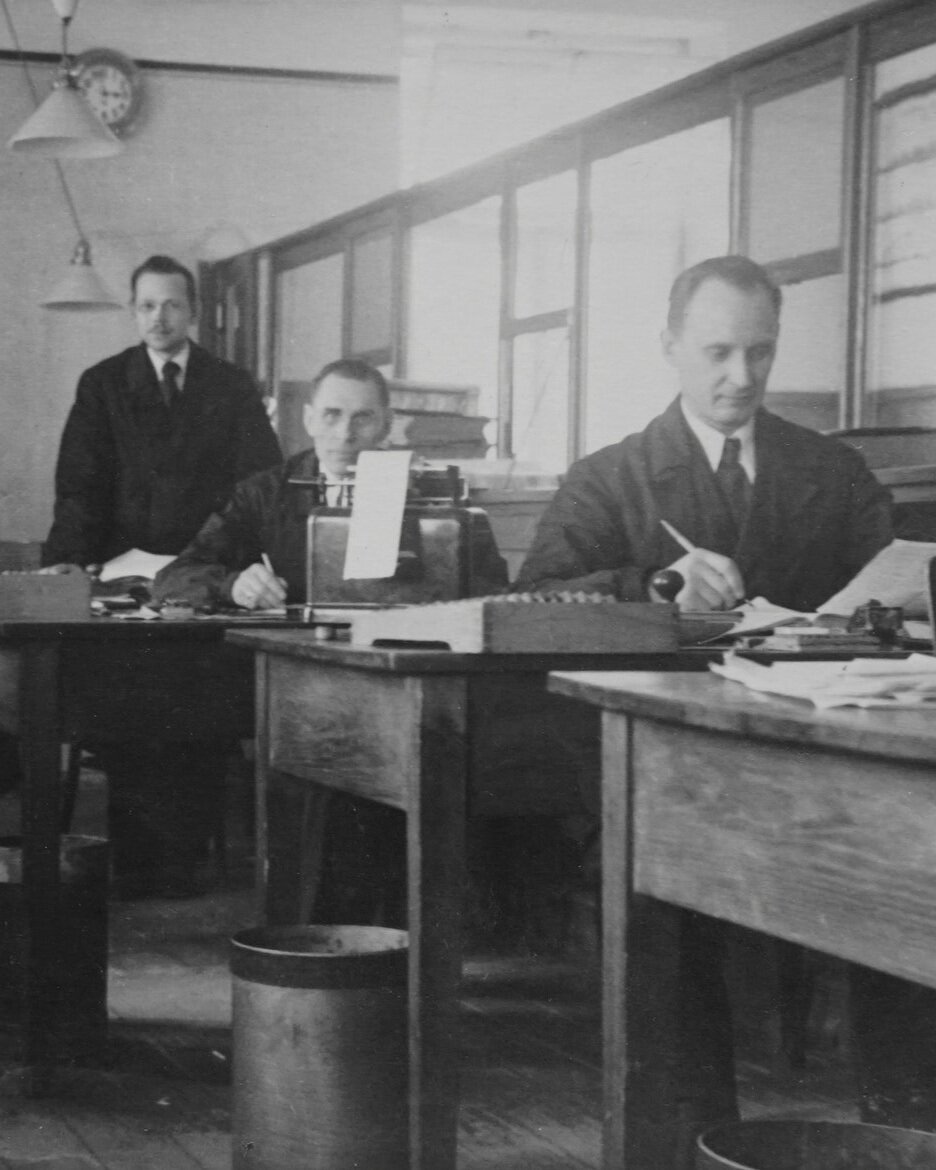

The offices of the commodities firm I’d been hired to work for were situated on two floors with a wide carpeted staircase connecting them. Administrative -- people like me -- were on top, while the sales force worked down below. In the beginning I kept to my confines. Truthfully, I was overworked, having to write one report after the other, and didn’t have time to wander around the premises.

But eventually curiosity got the better of me. I’d overhear Hank on the phone in his office next door talking about how the feds might be about to investigate the firm (these conversations were muffled; I’d maybe catch every third word, so I didn’t know whether to become actively worried or not). Occasionally I’d see Ron Schaeffer drifting down the hall like a ghost in his ill-fitting grey suit. But who were the rest of the people in this place? I started going downstairs to find out.

The sales guys were in a big open room, each with their own desk and phone, seated close to one another as if for inspiration. There were about twelve of them, all men, which seemed strange until I learned that people at the other end of a cold call seemed to have more faith in a male voice when it came to parting with their money. I’d go downstairs to visit and the guys would holler and cheer as if I were a visiting celebrity. “Let’s hear it for Nicole!” they’d shout, and my face would go beet red because I wasn’t used to that much attention. But to them I was indeed a Very Important Person, the one who gave them the information they needed to make their calls. Me, who knew nothing about finance! Suddenly, because of the trade journals I was constantly poring over, I was an expert who could advise them on how to pitch gold, copper, sugar, corn, soybeans, oil … what a joke!

Image: Bermix Studio

But it wasn’t really a joke because my name was on the firm’s materials -- all the reports I’d written -- and if the company did actually get in trouble with the feds (as was rumored) I could go down the tubes right along with them.

It didn’t help that the methods the sales team used to close deals over the phone were highly dubious. Sometimes I’d go downstairs just to watch them in action. They’d sweet talk clients, put on accents because a German or British-sounding voice inspired more confidence than a regular American accent. “Hang on a little sec, Betty Sue,” one of them would croon. “We've just had a newsflash on sugar that’s amazing and I need to check with our experts. You could make a bundle on this one!” Then he’d cover the mouthpiece and start talking to the guy at the next desk about what his wife was making for dinner that night or where they should go for lunch. When he returned to Betty Sue on the phone, he’d say, “It’s just like I thought! This is the perfect time to buy! You stand to make a cool $200 just on this one deal.”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry at the audacity of it.

Image: Anton Darius

In the meanwhile, the rest of my life was going pretty well. Jofka and I had moved out of the large, forbidding house on Fayerweather Street and were living in a second floor apartment on a narrow street of closely-spaced houses. Our landlady, an elderly woman named Mary who worked as a house cleaner and had pitchblack dyed hair and the droopy, scrunched-up face of a witch, forever sat guard on the front porch, making me nervous as I dug around in my bag for my keys or lugged groceries from the car up the front steps.

Our first morning in the place, Jofka and I had been awakened by a male voice yelling, “Eat your fuckin’ Cheerios or else!” Or else what? The voice was very rough and seemed to be coming from the kitchen. But when I jumped out of bed to check, I realized the voice belonged to our neighbor (actually our neighbor’s boyfriend, Manny) and that our windows, across the narrow concrete passage that separated the houses, were so close we might as well have been in the same room. Later I was to become fond of Manny, a car mechanic who kept my little Toyota running and who regularly fished for lobster and brought home a sufficient amount of coke for friends and neighbors to stop by and snort a few lines. But in the beginning all I knew was that my neighbor, a tiny redheaded woman about my age, had six children, an ex husband who visited every day, and a good looking boyfriend who’d slip out the back door the moment the ex arrived.

That was where I was when I started work at the commodities firm. I loved the apartment, which had two nice-sized bedrooms for Jofka and me, and a pretty study with a wide desk overlooking the street.

Carl moved in with us right around the time I interviewed for the job. He and I were in the same therapy group -- in fact, we’d joined the same day, three years earlier.

He was a pleasant-looking man in his late thirties who drove an ancient white Mercedes, favored short sleeved cotton shirts, and had some sort of complicated job at MIT. I liked him. A lot. But I wasn’t in love with him -- just really enjoyed his company. We had somewhat similar backgrounds in that his family, like mine, had had to flee Nazi Germany. He was endlessly curious and I could talk to him about anything under the sun. And he liked my parents, not the easiest people, whom we drove down to New York to meet one bright fall weekend. He also was crazy about Jofka, not trying to become an instant daddy, like some men I dated, but talking to her naturally, like an interested, older friend. We were happy and well-suited and we flirted a little during those early days with the idea of marriage. The only problem was, he drank too much.

Image: Kelly Sikkema

Image: Mathilde Langevin

It’s hard to say who was more in trouble with booze, me or my new live-in boyfriend, Carl. Our relationship, I think, was based on the pleasure we both took in drinking large amounts of alcohol and chit chatting late into the night. We would buy big cheap jugs of wine and go through them, pouring glass after glass, in a matter of hours. How much fun this was for us! Slurring our words, we’d wax poetic on a report I was writing or a situation that had come up for Carl at work. Jofka would have been put to bed much earlier in the evening, so we’d be free to act like the drunken fools we were, repeating the same stories over and over again, knocking over plates of food, sometimes even falling down. One night I tripped coming out of the bathroom, which was situated at the top of a back stairway leading to the back yard, and fell down the whole flight, landing at the bottom and looking around, perplexed. What had just happened? I was in a drunken stupor, so I didn’t really understand. All I knew was that I’d damaged my hand and my thumb (which was sprained) really hurt.

That’s the way things were, night after night. After a while, I tired of the whole situation and broke up with Carl. The endless drinking had gotten to me even though I, myself, was a terrible drunk. Once he was gone, I missed him; we’d been lovers and good friends and all my friends adored him, but I somehow had the sense to know the relationship was doomed from the start because of the way we both abused alcohol.

And yet, we remained close. We’d been in the same therapy group almost the entire four years I’d lived in Cambridge. We’d started on the same exact day and by some weird synchronicity we left on the same day, two active alcoholics who sat on the sidelines and rarely contributed.

No one in that group knew I drank till I passed out every night or that I drove drunk or that I had debilitating blackouts that caused me to have no memory of how I’d gotten home from a party or where I’d parked my car.

No one knew that Carl and I had had a love affair or that he had the same agonizing problems with booze that I did. It should have been obvious from the baggy-eyed, hungover looks on our faces, the somewhat graceless way we moved our bodies. But no one guessed. The therapist leading the group seemed particularly clueless and the fact that he didn’t pick up on the troubles of two of his more damaged clients was a real indictment of his skills as a psychologist. Looking back, I wonder why I stayed in the group so long. I certainly didn’t get much out of it. One of the members, an engineer in his early thirties who had trouble coping with depression, took his life swallowing a bottle of pills one day, the therapist calling each of us and saying in a subdued voice that Eric had killed himself. This was shocking, but I continued on for a few months. The last day I was in the group was the last day I ever saw Carl. As I said before, it was his last day too, and we kissed goodbye in the parking lot, holding onto one another for a few moments before parting for good.

Image: Zou Meng

This story was originally published in six parts in September and October 2021 on nicolejeffords.com.

Cover Image: Wilhelm Gunkel